What do you do with a mature landscape that is past its prime? There is always the option of tearing everything out and starting from scratch, but that may not be the best option. Think of the features of an established garden that can only be accomplished through time and patience. Soaring, mature trees provide cooling summer shade. The soil microflora and fauna are optimally balanced to support preferred shrubs and perennials. While it may be difficult to edit an existing landscape, you will be able to leverage the advantages of a mature garden to achieve superior results.

How do you know when it is time to edit an aging landscape? It is the right time when you feel that maintenance of your garden has become too demanding, you’ve outgrown former aesthetic decisions, or your lifestyle is changing and you want your garden to reflect the shift of your priorities. The clearest sign is that many of the landscape elements feel tired, overly stressed or just plain kaput.

Take a look at your landscape and identify what elements are working in your favor. Your garden may have a great framework of evergreen shrubs, beautiful deciduous azaleas that burst into color every spring, or a stunning Japanese maple that is the envy of your neighbors. Earmark these elements for preservation or enhancement. Even if some trees or shrubs seem overgrown, professional pruning can transform plants that feel out of scale. Keep in mind that you can successively transplant healthy plants to different areas (read more on transplanting here.)

If you have been living in your mature landscape for some time, then you are already intimately familiar with your garden. You know the special places, where you like to sit quietly, which areas attract gatherings of friends and family, and so on. In essence you know how you like to live in your garden. But sometimes it is that very familiarity that keeps you from recognizing how your landscape is fighting against the way you truly want to live. Emotional attachments to plants that have outlived their natural lives hold you back from making necessary changes. You may need an outside eye to evaluate your landscape with an unbiased point of view. To successfully edit your garden, it is critical to identify both the positive and problem areas. This is how we guide our clients through the editing process.

Even without a complete rebuild, it is still possible to rethink the overall organization of landscape spaces. Try to break away from “how it’s always been.” Examination with a critical eye may reveal alternative design solutions – and that is what we do best.

We at Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects recently attended a wonderfully useful lecture organized and sponsored by the Willamette Valley chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). Michel Wiman of Earthfort shared enlightening information, and in turn we thought we would share some highlights with our readers and followers.

First, we must point out that the scientific community is always learning more about the organisms that participate in the soil food web. However, we can apply what knowledge we do have to approach soil management biologically rather than chemically. Soil is absolutely teeming with living things. We can generally break up the organisms into three groups: macrofauna, which include animals like centipedes, voles, earthworms, and snails, mesofauna, which include microscopic worms called nematodes, protozoa, and pathogens, and microorganisms, which include bacteria and fungi. Realizing that soil is anything but a sterile environment should also help us to realize that gardening is a cooperative process.

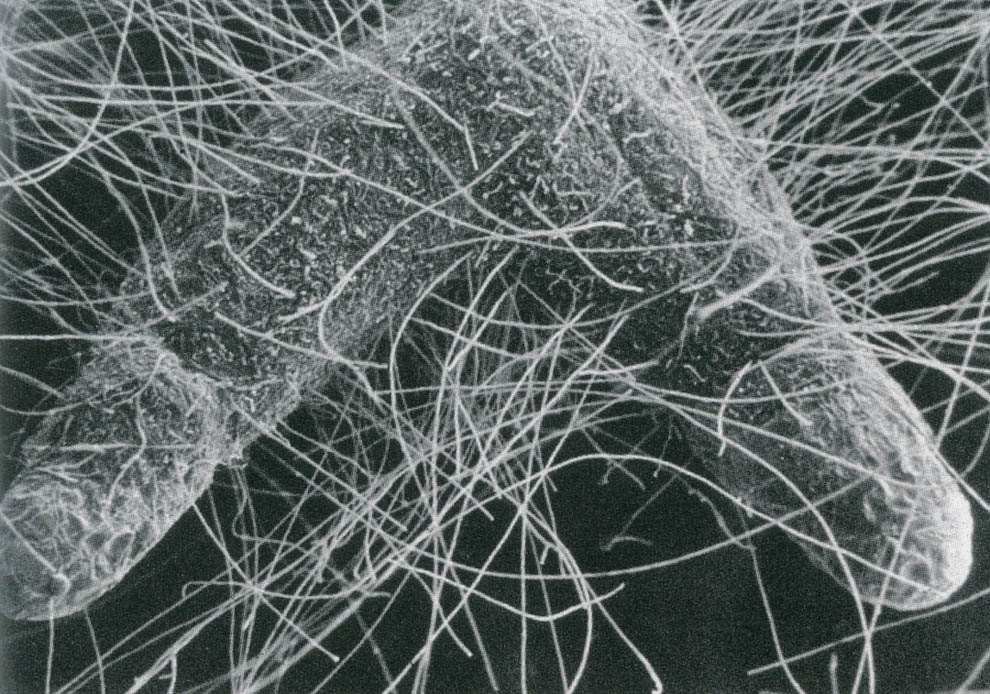

For example, did you know that the relative proportion of fungi to bacteria affects the pH of soil? Tilling the soil your planting beds sets the soil to a bacterially dominated and alkaline habitat, which favors early successional plants, being primarily what we consider “weeds.” Trees, shrubs and later successional perennials, the kinds of plants we typically want to thrive in our gardens, prefer the acidic environments of fungi dominated soils. The presence of fungi encourages mycorrhizal associations, which are critical to the function of a plant’s nutrient uptake. If we break up the word “mycorrhiza” into its constitutive parts – “myco” meaning fungus and “rhiza” meaning root – it is easier to remember that a mycorrhizal association is simply a mutually beneficial relationship formed by a fungus and a plant. Mycorrhizal filament growth allow plants to reach beyond their root depletion zone, accessing nutrients that would otherwise be beyond reach.

This example illustrates that the flora and fauna living of the soil have specific roles in the health of that soil. Protozoa help to decompose organic material, earthworms aerate the soil, and predatory nematodes kill pest insects. Which leads us to the idea of integrated pest management (IPM). IPM favors biological based intervention over chemical control. Chemical approaches to controlling pests create vacuums in nature. Spraying to eradicate a species of pest insect may successfully eradicate most of the individual pests. However, those that are resistant to the control will quickly reproduce to take advantage of the biological vacuum, therefore rendering the chemical control useless. IPM advocates management to eliminate vacuums. It looks to suppress pests by targeting sensitive stages of the pest’s life cycle, thereby reducing populations to a level that does not cause harmful effects. The crux of IPM is being in touch with what’s happening in your soil. Monitoring and identifying pest activity is crucial, and it does involve additional time and effort.

We think that this base knowledge of the inner workings of living soil has a cascading effect how we view and interact with our gardens. Of course, there is always more to learn and the folks at Earthfort are an incredible resource. Additionally, if you want to learn more from home, the UC Davis IPM website is a great place to start.

When we came across Anne Raver’s article “Asking More of the Landscape,” which recently appeared in the New York Times, we were reminded of the multitude of intertwining factors that we must always keep in the forefront of our minds as landscape architects. One excerpt in particular stands out. Douglas Tallamy, co-author of the recently published book The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, points out that, “in the past, we have asked one thing of our gardens: that they be pretty. Now they have to support life, sequester carbon, feed pollinators, and manage water.” We could even make additions to that list. Our design ethos also demands that we ask gardens to be livable spaces that meet the needs and wants of our clients.

The much welcomed winter blooms of the witch hazel, daphne, quince, and sarcococca remind us all that spring is fast approaching. Proper preparation for a thriving growing season requires that like landscape architects, you should think of several parallel processes at once.

Soil preparation will be the foundation of landscape success or failure. If you are planning to add a new spring planting, it is crucial to conduct soil testing to determine the appropriate soil amendments. Resources on the Oregon State Extension website thoroughly detail how to collect soil samples (http://extension.oregonstate.edu/gardening/node/937). The extension service also provides listings for local laboratories specializing in soil analysis.

The correct timing of soil amendment and turning adds another layer of complexity. You must add amendments with enough lead time to allow the soil to settle. Turn the soil too early and you may compact the soil and negatively impact the soil structure. Turn the soil too late and you will be in for a season of preventable, additional watering. Many strategies advocate not turning the soil at all, but layering on top of native soil with compost.

While thinking about all of the above, also consider that late winter is the time to finalize planting design. In what will seem like no time, the nurseries will be full of choice perennials and ideal structural plants. If you do execute a spring planting, you will at least need some kind of temporary irrigation strategy. With our dry summers, even native plants adapted to the Willamette Valley will require irrigation for the first one to two years of establishment. Getting your planting plans in order now will give you enough time to plan for irrigation requirements.

Believe it or not, this juggling of simultaneous timelines and to-do lists is fun for us. We’d love to share our years of training and gardening experience to help you sort through strategies for a thriving, symbiotic, functional…and yes, pretty… garden.