As the weather warms up here in Eugene, Oregon, we enjoy spending more time outside. For most homeowners, the privacy of a back yard provides the greatest opportunity for relaxation and enjoyment, while the front yard remains more formal and primarily serves as space for circulation. Despite the more public nature of the front yard, we at Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects believe it is a rich canvas for outdoor living. Let’s delve into this frequently viewed but often overlooked space.

When visitors approach a house, the front yard is the first introduction to the home. It prepares guests for the character of the individual homeowner and responds to the vernacular of the neighborhood. Context plays a strong role in the perception of a front yard; an aesthetic that ties into the surrounding properties creates a powerful sense of neighborhood cohesion. The front yard also gives homeowners an opportunity to express their values to the public. A xeriscape or vegetable garden in the front yard communicates sustainable principles, and is all the more visible amidst a sea of lawns. A more subtle transition from the context, such as a turf-alternative like micro-clover, can create a dialogue with the neighbors and minimize the need for irrigation. Lawn space lends a serene respite and is a valuable element in design; however, the front yard can provide a richer experience when that lawn is thoughtfully combined with other types of vegetation.

While front gardens are generally considered a counterpoint to the more private back garden, not every property has an equal balance between these two realms. Corner lots or lots with large building setbacks often result in homes with ample front yards and meager or nonexistent back yards. In these instances, the role of the front yard should evolve to serve more private functions. Subdividing the garden space – either through careful arrangement of plants or through fences and hardscaping – can create outdoor rooms that extend privacy into the front space.

The front yard also is a valuable opportunity to physically and mentally transition from the public realm to the private realm. In a previous blog post, we explored the power of thresholds in creating meaningful outdoor rooms and transitioning into more personal spaces. The front garden is rich with design opportunities to shed the pressures of the larger world as you move toward the home. Close attention to the solar aspect and surrounding vegetation will help define the character and clarity of the entry, as will carefully choreographed outdoor lighting. The presence of vehicles strongly affects the cohesion of the front yard and entry experience; providing some separation between the car and the entrance to the home will preserve the serenity of the home, while maintaining ease of access is important for function. Thoughtfully balancing the many needs placed on the front yard results in a space that is simultaneously welcoming and thoroughly usable, expressing the personality of the homeowner and engaging with the character of the surrounding neighborhood.

Is this harsh winter weather giving you a bit of cabin fever and making you hunger for garden time? It’s a great time to start dreaming, but while you are stuck indoors, take the time to appreciate the architectural qualities of your home. A truly integrated garden will reflect the style and proportion of the architecture in the outdoor experience. We have written before about the role outdoor spaces play in providing beautiful and functional outdoor rooms; however, gardens can enhance the expression of your home in other ways.

Complement your home by paying close attention to the proportion and scale of the house, and extend those same design principles in your landscape. For example, tall evergreen trees that would dwarf a single-story bungalow can provide an appropriately scaled backdrop to a larger home. Likewise, if you have a large central room in your home, looking out onto a similarly proportioned outdoor space extends the indoor experience – visually in the winter and physically in the summer. It creates a harmonious composition, marrying the home and the garden. The use of similar proportions of space supports the continuity between the architecture and the garden.

In addition to mirroring the proportions of interior spaces, the composition of views from inside to out complements and supports the interior design. Each window is a landscape painting that adds character to your home throughout the year. Trees with sculptural branches, flowering plants and evergreen elements are living art that communicate the inherent beauty of the seasons. The orchestration of textures, sizes, and annual transformations of plants frames desirable views and camouflages the things you’d like to ignore. Artful lighting expresses additional dimensions, supplying glow and sparkle after the sun sets.

Plants can be used to extend the architectural lines of your house, focusing views on important architectural elements such as entryways. Evergreen hedges extend walls, tree trunks and narrow conifers march rows of columns out into the landscape. The simple choice of plants that will not exceed the heights of ornamental elements like windows or molding is often overlooked. Conversely, filmy foliage and contrasting textures can add depth and interest while hiding utilitarian spaces or weak architectural elements.

When the architecture of a home strongly expresses the style of a particular period or region, there is always a corresponding genre of plant palette and stylistic use. Mimicking these garden expressions is a very sophisticated way to emphasize the architecture. A good primer for historical homes is Favretti’s book, For Every House a Garden. This text explores both compositional strategies and period-authentic plants that were used in American garden design from colonial times through the 1940s. While a to-the-letter historical approach may seem intimidating, this is a particular passion of ours and where authenticity is a priority, we are happy to explore this with you. Plants can also enhance the expression of a regional style – such as figs and rosemary for a Mediterranean home, olives and lavender for a Provencal style house, or bold graphic textures for a mid-century modern building. Simply employing construction materials that are from the palette of the home – such as brick, exposed timbers, ornate ironwork, clean concrete forms etc. – when designing the outdoor spaces can harmonize with the architecture in a few simple moves.

While these strategies are excellent to complement and emphasize the architectural style of your home, what happens if the style of the house falls flat for you? Landscape design provides a great avenue to add personality to your house if you feel it is lacking. A well planted garden can soften a stark façade, while added outdoor elements like trellises or arbors can add depth and character to a less-detailed exterior. A thoughtful landscape design that fully considers the existing architecture, style and proportion, adds color and life well beyond the limitations of the walls of the house, and expresses the unique character of every home and the people who inhabit it. Here at Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, the interplay between the home and garden is our passion, and we would love to help you start planning your landscape as we eagerly await the spring.

Do you ever reach the rainy months feeling like you missed out on your summer outdoor experience? Summer in Eugene is the time when our gardens truly shine; they inspire us to spend time outside and serve as everything from a restful retreat to a place for hosting dinner parties and cookouts. Whether you treasure the quiet respite of a solitary cup of tea or coffee in the morning or the bustling activity of a group event, the summer garden invites us to live and dine outdoors and savor the summer weather. Have you ever wondered how your garden design could improve your outdoor dining experience? Winter is a perfect time to plan your garden redesign. In a previous post, we explored the potential for a garden to supply food: this one investigates the many ways we bring our food into the landscape, and how the design of spaces can encourage outdoor dining.

Outdoor dining means different things for different people. Many of us relish the experience of cooking food outdoors during the summertime; it saves our homes from the heat of cooking and ties to our nostalgia of picnics and barbecues. For some, the Fourth of July and Labor Day would not be the same without a cookout. But how can our landscapes support us to cook or eat outside, and offer a functional cooking and dining experience?

One way to customize a garden for outdoor cooking is to create a space for the ritual of food preparation. Too often, gardens allow space for a grill without any surrounding support spaces, and we find ourselves trekking between home and garden as we cook. Carefully tailoring the outdoor space to allow workspace near the grill is a simple step that makes outdoor cooking easier. Likewise, a cooking area surrounded with edible plants creates an integrated garden for harvest and cooking.

For those who prefer the convenience of a full kitchen in the house, eating outside is still wonderful in the warm, dry months. As you plan your outdoor living spaces, consider – do you want to create an intimate space that invites more solitary retreat? Or do you want to host a garden party for a group of friends? Flexible gardens with these considerations in mind will give a platform for outdoor dining that meets your current desires but can adapt to future needs, and make pockets of space for a variety of uses. Rather than creating a single large hardscaped area, consider mixing permeable paving and lawn into your dining area to create more adaptable spaces that can expand to suit your needs without overwhelming a small group. Similarly, a carefully orchestrated lighting design will provide both intimate ambiance and broad-reaching illumination to support an array of events. Even small spaces can be wonderful outdoor rooms.

At Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, we consider the garden as an extension of the home, and view outdoor spaces as an opportunity to increase the function and beauty of the way you live. Outdoor terraces, porches, decks, and lawns become rooms to inhabit in the summer months, and are some of the building blocks of our designs. As you imagine better outdoor dining options, we are happy to help make your garden into a beautiful and functional place in time for the next summer season.

It’s October, and many plants here in the Eugene, Oregon area are going dormant for the winter. This is the time of year that we really begin to appreciate our evergreen plants. While they bring life to our gardens throughout the seasons, the prominence and character of evergreens in a planting design can shift throughout the year. Evergreens often play a supporting role to the exuberance of summer blooms, providing a subtle backdrop that recedes until other plants begin to go dormant. We rely upon their winter foliage to provide privacy, interest and contrast. Creating a harmonious planting plan that balances evergreens with deciduous and flowering plants is critical to providing year-round appeal and creating interesting outdoor spaces.

When picturing an evergreen many people imagine a coniferous tree, such as the iconic Douglas Fir that grows throughout the Pacific Northwest. However, the term evergreen encompasses a diverse range of broad-leafed and coniferous trees and shrubs – including many native species - that retain their foliage over the winter. While dark green foliage is common in evergreens, you can add a wide array of color to your garden with evergreen trees and shrubs. Abelia, Leucothoe, Oregon Grape, and Nandina all provide a myriad of hues, from yellows and greens to reds and purples. Plants such as Cotoneasters and Holly have bright berries that add punctuation to their evergreen foliage. Evergreens can also bring many different textures to your garden. Some leaves, such as those of Japanese Fatsia, are large and tropical, while others provide much filmier and small texture, such as Bamboo. Because they persist throughout the year, evergreens play a vital role in creating the character of your landscape architecture.

There are few times that we appreciate evergreens more than in the wintertime. Many plants remain dormant in the winter, leaving browned foliage and bare twigs that seem desolate. Evergreen plants help maintain appeal during the winter months, bringing much-needed color and life to our landscapes. These plants are deeply entwined in our wintertime traditions – many cultures bring in cut boughs during the winter month to symbolize life and health. The smell of pine and fir needles evokes a sense of comfort on a cold winter day.

In the winter garden, evergreens also provide us with privacy and shelter. Hedges are often created with evergreen plants, which offer screening throughout the year. Traditional gardens use Boxwood or Privet for hedges, but many evergreens will tolerate pruning and hedging with grace, and may provide a more casual aesthetic. Choosing to use a hedge for privacy does not need to limit or define the aesthetic style of your garden. Additionally, whether in straight lines or clusters, evergreens buffer wind speeds in a garden, creating calmer microclimates on blustery winter days.

While winter and fall may be the time that evergreen plants shine, they play a vital role throughout the year. The evergreen elements provide continuity throughout the seasons; therefore, they are especially useful in structuring your garden. Using evergreen plants around the edges of your garden will help ensure that it remains well-defined even as the more ephemeral plants lie dormant. Those same edges will act as a backdrop, providing a calm foil for the more showy flowering plants that emerge in spring and summer. As the season progresses, the deep greens of evergreen foliage set off the vibrant hues of fall foliage. Light colored bark – such as Birch tree bark – takes center stage when set against a dark evergreen background. Similarly, the bright stems of Red Twig Dogwoods sparkle against the darker foliage.

Though the role of evergreens in your landscape architecture may evolve through the seasons, their presence provides critical structure and continuity to your garden. Most gardens benefit from the addition of seasonal interest and vibrancy that perennials and flowering plants bring, but they benefit equally from the stability and continuity of evergreens. Successful gardens harness a carefully considered palette of evergreen and deciduous plants to provide interest across the seasons. Achieving a proper balance in planting is one of the most challenging and rewarding aspects of creating an inviting landscape, and is something that we love to work with at Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects. As we enter the fall and wintertime season, it is a great time to think about structure in your garden and how evergreens will liven up your space.

As the days lengthen and the weather warms here in Eugene, Oregon , we are excited by the approach of summer. Farmer’s markets laden with produce and gardens bursting with abundance go hand-in-hand with these sunny days. Eugene has an ideal climate for food production, and the benefits of growing edible plants are numerous. This is the perfect time of year to start establishing a vegetable garden. While this process may seem intimidating, there are many ways you can incorporate edibles into any size or style of garden.

Raised beds are a tidy and easy form of vegetable gardening. This method allows the gardener to import and amend better soil, and is productive in small areas. Raised beds also are easier to weed and maintain. Tidy rows of crops harken strongly to agricultural aesthetics. The familiar and homey look of dedicated vegetable beds satisfies our desire to raise our own food, and the taste of freshly harvested veggies is unparalleled. For the more casual gardener, edible crops can also be integrated into flower gardens and can provide exceptional ornamental value.

Beds of mixed ornamental and vegetable crops are a great way to create a multi-functional garden without the commitment of a dedicated vegetable area. Many of our edible crops also have excellent aesthetic value. Tuscan kale, artichokes, and rhubarb provide architectural interest with their bold texture and structured foliage. Herbs like dill and parsley bring light frothy textures to the garden. Fig trees have sculptural form, attractive bold foliage, and provide fruit in the late summer months. Many fruit- and nut-bearing trees have striking flowers in the spring months. Blueberry shrubs have interest that spans many seasons, from spring blossoms to summer fruits, with bright fall color and red twigs in winter. Raspberries can be trained along fences to visually soften the edges of the garden and provide summertime fruits, while espaliered fruit trees create a formal, cultivated aesthetic at the garden edge. Many edible crops also provide valuable food sources for pollinators, which is of significant benefit to other plants and gardens, as well as the heath of the pollinator population.

For the smallest gardens or for individuals just starting to experiment with edible crops, container gardening provides an opportunity to grow food crops in a tiny footprint. Many vegetables and herbs –including tomatoes - are well-suited to growing in containers, and nurseries are continually developing dwarf berry plants and other fruit-bearing crops that can thrive in containers.

Edible gardening is unique in its flexibility and adaptability to many scales and aesthetics. Layout of an edible garden can be an art form, and balancing productive space with areas for ornamental plants and outdoor living can pose a challenge for many homeowners. At Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, we can help you balance these complex interactions and create a space that is welcoming, engaging, healthy and delicious.

In every domestic landscape, there are moments of entry – thresholds that separate the personal realm from the public. Whether these thresholds are explicit or more subtle, they shape the experience and rhythm of outdoor space. In landscape design, thresholds create unique opportunities to register a moment in time. They guide us through the landscape and concentrate a transition between two realms. Thoughtful thresholds will make meaningful connections between spaces and enrich the garden experience.

Good spatial definition creates intentional outdoor rooms. The transitions that link these rooms help set the tone for the space. While arches and gates form literal entrances, plants are a great tool for implying edges and transitions. In the temperate climate of Eugene, Oregon, many different plant species thrive. This produces a rich palette from which gardeners can choose specimens that define the character of a space. To create a formal entrance, the vertical structures of conifers will act as gateposts to the garden. Trees with branches that join overhead create gateways. Small multi-trunked trees such as vine maples or witch hazels framing a path provide a more whimsical introduction.

While trees and other vertical elements are useful markers, the ground plane creates another opportunity to articulate transitions. A change in materials underfoot can slow movement or mark a change in space. The crunch of a gravel walkway contrasts with a smooth paved surface, articulating a change in space.

Thresholds are more than a simple link between two spaces. They choreograph the experience of moving through the garden. They help create separation between the public and private realm, providing a heightened sense of arrival to the domestic sphere. A well-designed threshold extends the boundaries of the home into the garden. These transitions help you shed the static of everyday life as you leave the car behind and enter the sanctuary of the home.

Positioning thresholds carefully will frame views and draw you through space. Highlighting a beautiful destination with a constricted opening creates intrigue and an invitation through the garden. Thresholds create contrasts - between open and enclosed spaces, between light and dark, public and private – and compress that contrast into a single moment. This compression heightens awareness and defines space. Thresholds are an important ingredient in creating comfortable outdoor spaces, and are carefully crafted at Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects.

It’s March, and the rich scent of daphne punctuates the air as the first season of flowers bloom here in Eugene, Oregon. For many, daphne’s fragrance evokes the first teasing hints of spring. Above all other sensory experiences, scent has the power to conjure memory, triggering associations and adding depth to the present moment. It is elusive and yet ever present, from sweet floral notes of lilies and jasmine to the piercing greenness of freshly cut grass; from crisp autumn leaves and wood smoke to the rich dampness of rainfall. These scents permeate both our landscapes and our memories, inherently linked to seasonality. They represent experiences that are shared across backgrounds as well as unique personal moments. When carefully integrated into landscape designs, scented plants add richness and vibrancy throughout the seasons.

Fragrance can be harnessed in a design for many purposes. A particular scent can change your frame of mind or underscore the character of an outdoor room. For example, if you brush past the aromatic foliage of rosemary or lavender, they create a warm and soothing backdrop to the experience. Corsican mint underfoot makes an otherwise hot and sunny landscape seem cooler and more refreshing in the height of summer. Scents help transition from the hustle of everyday life into the peaceful space of the garden.

Careful crafting of spaces will enhance the sensory experience. Many scents are most pronounced in still air, so a garden enclosed by fences or vegetation will emphasize fragrance more than an open area. Designs that orchestrate the timing of a fragrance with the use of outdoor space maximize the impact of scents in a garden. Fragrant plants with early bloom times are especially welcome near a sunny place that is pleasant in the spring, while aromas near shadier spaces are better enjoyed in the hot summer months. Scents can be savored near places to pause and reflect, such as benches or gateways.

The role of fragrant plants is not limited to outdoor spaces. Strategic placement of scented plants will create fluidity between indoors and out. A fragrant plant near a window brings the garden into the home. A cutting garden will provide scented blossoms even if the weather discourages outdoor living. These sensory experiences anchor us in the present moment; they link us to the seasonal fluctuations in our lives, even as they harken to seasons past. At Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, scent is one of our favorite tools in crafting outdoor rooms, and we would love to help you incorporate fragrant plants into your landscape. Stop and smell the roses.

To cultivate a successful, self-sustaining orchard, you will need craft a strategy that balances interconnecting landscape considerations. The first step is to analyze your property to select the most optimal location for your future orchard. The key ingredient for a successful crop and healthy trees is an ideal microclimate. Of course fruit and nut trees require steady sun exposure, but they also need positive air movement. It is imperative to shape a space for your orchard where cold, moist air will not stagnate and collect.

The layout and individual placement of your trees have much to do with encouraging beneficial air flow. The popular quincunx pattern persists through the ages because the trees are spaced equally apart, allowing each an equal share of soil nutrients while keeping a healthy distance between each individual tree. The aesthetic quality of a quincunx pattern adds to its appeal. It is the quincunx pattern that produces the magical experience of trees repeatedly snapping into perfect geometry as you move through and around an orchard.

The layout and individual placement of your trees have much to do with encouraging beneficial air flow. The popular quincunx pattern persists through the ages because the trees are spaced equally apart, allowing each an equal share of soil nutrients while keeping a healthy distance between each individual tree. The aesthetic quality of a quincunx pattern adds to its appeal. It is the quincunx pattern that produces the magical experience of trees repeatedly snapping into perfect geometry as you move through and around an orchard.

You must also consider the fertilization requirements of your selected trees. Some species of fruit trees require a pollination partner within close proximity in order to produce a good crop. Clearly, this information must be folded into the ultimate layout. Portland Nurseries produces useful reference guides that will help with choosing appropriate pollination partners.

To save space, you may choose self-fertile trees that do not require partners. Another strategy is to choose a family tree, which has different varieties grafted onto one rootstock. In Britain, a dedicated horticulturalist has managed to graft 250 different apple varieties onto one single tree!

Finally, think about how you want to choreograph your harvest. Do you want to time your harvest so that you receive a steady stream of fruit throughout the season? Or are you an avid canner or brewer who wants all the harvest to come in at once?

Obviously, this is a lot to wrap your brain around. Keep in mind that we can help with this complex business of orchard planning, especially if your orchard plans become the seed of inspiration for a larger reorganization of your landscape.

Does something flutter in your stomach when you drive past the straight lines and orderly patterns of an orchard? Do you love taking home an entire bushel of locally grown apples from your favorite pick-your-own orchard? If you find yourself nodding yes in response, a part of you must long for an orchard of your own. And you’re not alone. Many of us who live in the Willamette Valley desire to be part-time orchardists. During peak harvest times, Eugene is absolutely bursting with a bounty of apples, pears, filberts, cherries, plums, figs, and apricots.

But why is it that we Eugenians feel such an affinity towards orchards?

Homesteading on rural, suburban, and urban plots is particularly popular in our neck of the woods. Perhaps striving for self-reliance and sustainability appeals to our pioneer spirits. Perhaps it’s as simple as knowing that the food you grow yourself tastes better than anything you could buy at a store. There’s something about participating in a harvest that keys us into the rhythm of the seasons. Growing our own fruit and nuts is not only gratifying, it tunes us to into the landscape on an altogether deeper level.

Orchards tickle the part of our hearts and minds that tap into our collective landscape memory. Stretching back into time, orchards have been tightly woven into the idea of a tended garden. In “The Garden of the High Official of Amenhotep,” one of the oldest paintings of a planned garden, we see that fruit trees were integral to the composition of ancient Egyptian gardens. The orderly layout of an orchard symbolized the Romans’ ordered sense of the world. Romans even worshipped a goddess named Pamona who tended and protected fruit trees and orchards.

Reminders of our landscape’s agricultural past are all around us. Pre’s Trail in Alton Baker Park winds through remnant filbert orchards. Dorris Ranch in Springfield is the oldest filbert orchard in the United States. These are the places that we love to revisit. The scale of the orchard trees is relatable to the human body. They do not soar high above us, making us feel small and diminished. When arranged in orchard rows, the branches of individual trees form an arching ceiling over our heads, sheltering and protecting us. The trees are nourishing both to our bodies and our spirits.

You don’t need an entire orchard evoke the same feeling. Even if there is just one remnant apple tree on your property, you can build upon and continue that legacy with space-saving techniques.

If you think you are ready to start your own orchard, now is the time. Fruit trees are available for purchase in local nurseries. Also stay tuned to our Facebook and Blog pages - an upcoming post will outline the interconnecting aspects of orchard cultivation that you will need to consider during your planning phase.

What do you do with a mature landscape that is past its prime? There is always the option of tearing everything out and starting from scratch, but that may not be the best option. Think of the features of an established garden that can only be accomplished through time and patience. Soaring, mature trees provide cooling summer shade. The soil microflora and fauna are optimally balanced to support preferred shrubs and perennials. While it may be difficult to edit an existing landscape, you will be able to leverage the advantages of a mature garden to achieve superior results.

How do you know when it is time to edit an aging landscape? It is the right time when you feel that maintenance of your garden has become too demanding, you’ve outgrown former aesthetic decisions, or your lifestyle is changing and you want your garden to reflect the shift of your priorities. The clearest sign is that many of the landscape elements feel tired, overly stressed or just plain kaput.

Take a look at your landscape and identify what elements are working in your favor. Your garden may have a great framework of evergreen shrubs, beautiful deciduous azaleas that burst into color every spring, or a stunning Japanese maple that is the envy of your neighbors. Earmark these elements for preservation or enhancement. Even if some trees or shrubs seem overgrown, professional pruning can transform plants that feel out of scale. Keep in mind that you can successively transplant healthy plants to different areas (read more on transplanting here.)

If you have been living in your mature landscape for some time, then you are already intimately familiar with your garden. You know the special places, where you like to sit quietly, which areas attract gatherings of friends and family, and so on. In essence you know how you like to live in your garden. But sometimes it is that very familiarity that keeps you from recognizing how your landscape is fighting against the way you truly want to live. Emotional attachments to plants that have outlived their natural lives hold you back from making necessary changes. You may need an outside eye to evaluate your landscape with an unbiased point of view. To successfully edit your garden, it is critical to identify both the positive and problem areas. This is how we guide our clients through the editing process.

Even without a complete rebuild, it is still possible to rethink the overall organization of landscape spaces. Try to break away from “how it’s always been.” Examination with a critical eye may reveal alternative design solutions – and that is what we do best.

We at Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects recently attended a wonderfully useful lecture organized and sponsored by the Willamette Valley chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). Michel Wiman of Earthfort shared enlightening information, and in turn we thought we would share some highlights with our readers and followers.

First, we must point out that the scientific community is always learning more about the organisms that participate in the soil food web. However, we can apply what knowledge we do have to approach soil management biologically rather than chemically. Soil is absolutely teeming with living things. We can generally break up the organisms into three groups: macrofauna, which include animals like centipedes, voles, earthworms, and snails, mesofauna, which include microscopic worms called nematodes, protozoa, and pathogens, and microorganisms, which include bacteria and fungi. Realizing that soil is anything but a sterile environment should also help us to realize that gardening is a cooperative process.

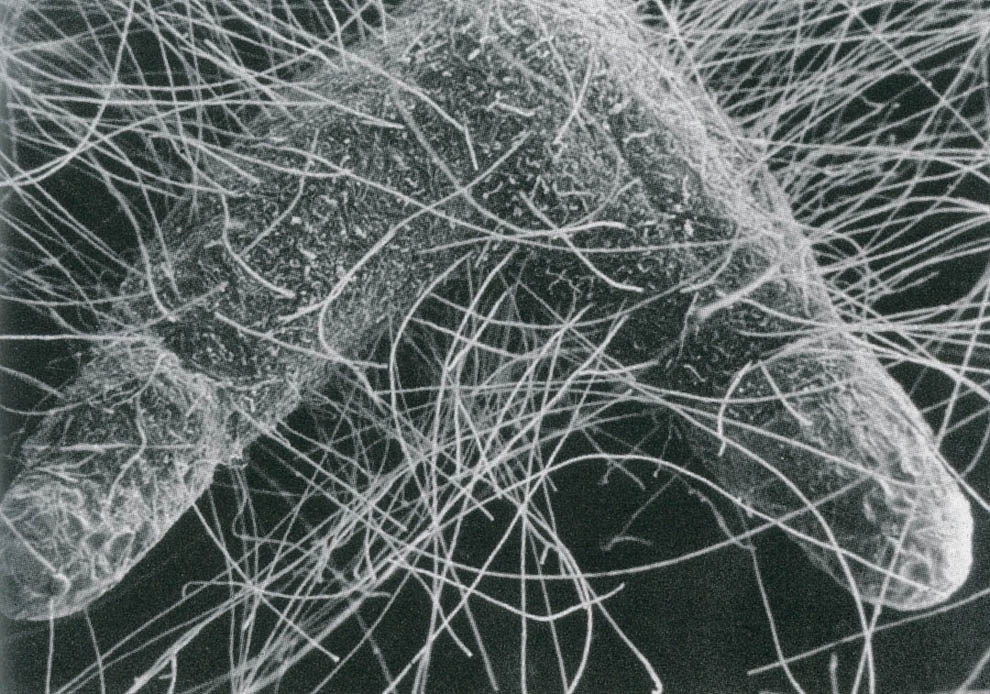

For example, did you know that the relative proportion of fungi to bacteria affects the pH of soil? Tilling the soil your planting beds sets the soil to a bacterially dominated and alkaline habitat, which favors early successional plants, being primarily what we consider “weeds.” Trees, shrubs and later successional perennials, the kinds of plants we typically want to thrive in our gardens, prefer the acidic environments of fungi dominated soils. The presence of fungi encourages mycorrhizal associations, which are critical to the function of a plant’s nutrient uptake. If we break up the word “mycorrhiza” into its constitutive parts – “myco” meaning fungus and “rhiza” meaning root – it is easier to remember that a mycorrhizal association is simply a mutually beneficial relationship formed by a fungus and a plant. Mycorrhizal filament growth allow plants to reach beyond their root depletion zone, accessing nutrients that would otherwise be beyond reach.

This example illustrates that the flora and fauna living of the soil have specific roles in the health of that soil. Protozoa help to decompose organic material, earthworms aerate the soil, and predatory nematodes kill pest insects. Which leads us to the idea of integrated pest management (IPM). IPM favors biological based intervention over chemical control. Chemical approaches to controlling pests create vacuums in nature. Spraying to eradicate a species of pest insect may successfully eradicate most of the individual pests. However, those that are resistant to the control will quickly reproduce to take advantage of the biological vacuum, therefore rendering the chemical control useless. IPM advocates management to eliminate vacuums. It looks to suppress pests by targeting sensitive stages of the pest’s life cycle, thereby reducing populations to a level that does not cause harmful effects. The crux of IPM is being in touch with what’s happening in your soil. Monitoring and identifying pest activity is crucial, and it does involve additional time and effort.

We think that this base knowledge of the inner workings of living soil has a cascading effect how we view and interact with our gardens. Of course, there is always more to learn and the folks at Earthfort are an incredible resource. Additionally, if you want to learn more from home, the UC Davis IPM website is a great place to start.

When we came across Anne Raver’s article “Asking More of the Landscape,” which recently appeared in the New York Times, we were reminded of the multitude of intertwining factors that we must always keep in the forefront of our minds as landscape architects. One excerpt in particular stands out. Douglas Tallamy, co-author of the recently published book The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, points out that, “in the past, we have asked one thing of our gardens: that they be pretty. Now they have to support life, sequester carbon, feed pollinators, and manage water.” We could even make additions to that list. Our design ethos also demands that we ask gardens to be livable spaces that meet the needs and wants of our clients.

The much welcomed winter blooms of the witch hazel, daphne, quince, and sarcococca remind us all that spring is fast approaching. Proper preparation for a thriving growing season requires that like landscape architects, you should think of several parallel processes at once.

Soil preparation will be the foundation of landscape success or failure. If you are planning to add a new spring planting, it is crucial to conduct soil testing to determine the appropriate soil amendments. Resources on the Oregon State Extension website thoroughly detail how to collect soil samples (http://extension.oregonstate.edu/gardening/node/937). The extension service also provides listings for local laboratories specializing in soil analysis.

The correct timing of soil amendment and turning adds another layer of complexity. You must add amendments with enough lead time to allow the soil to settle. Turn the soil too early and you may compact the soil and negatively impact the soil structure. Turn the soil too late and you will be in for a season of preventable, additional watering. Many strategies advocate not turning the soil at all, but layering on top of native soil with compost.

While thinking about all of the above, also consider that late winter is the time to finalize planting design. In what will seem like no time, the nurseries will be full of choice perennials and ideal structural plants. If you do execute a spring planting, you will at least need some kind of temporary irrigation strategy. With our dry summers, even native plants adapted to the Willamette Valley will require irrigation for the first one to two years of establishment. Getting your planting plans in order now will give you enough time to plan for irrigation requirements.

Believe it or not, this juggling of simultaneous timelines and to-do lists is fun for us. We’d love to share our years of training and gardening experience to help you sort through strategies for a thriving, symbiotic, functional…and yes, pretty… garden.

Now that the rainy days in Eugene outnumber the sunny, have you noticed wet patches and mud pits growing in your landscape? Ask yourself - do these mucky areas reappear every winter and keep you out of your garden all season long? An emergent sea of mud is more than an annoyance. Improper drainage results in unusable outdoor spaces. Bog-like conditions in areas of circulation such as walkways or paths can be dangerous – not to mention horribly messy as you move between the indoors and the out.

Perhaps when summer arrives and the water retreats, you forget about this reoccurring rainy season problem. But now that the wet has settled in for the foreseeable future, let’s take care of it once and for all.

Grading and drainage is a delicate art and best tackled by landscape architects. These rainy days provide opportunities for us to observe your landscape and identify the tell-tale signs of dysfunctional drainage. It is easy to see where water pools, but it is more difficult to understand why. We will brainstorm strategies to address drainage problems including soil amendment, sub-grade infrastructure, surface drains, and most importantly, grade manipulation. In many of our past projects, such as the Wiley Garden, we were able to design solutions that transformed constantly wet and uninviting outdoor areas into landscape rooms that you can actually live in all year long.

In Eugene the rain lasts for a long time, but Oregonians don't let rain derail productivity and forward progress. The winter is the ideal time to initiate the design process for your landscape. The rainy months allow the right amount of time for dreaming and scheming. We have found that the most successful designs begin with a clear vision of what it is that you want. Do you envision a garden bursting with color and vibrancy or do you dream of a tranquil retreat? A good way to get the creative juices flowing is to look for inspiration on sites like Houzz or Pinterest, in magazines like Landscape Architecture Magazine or Sunset, and in books. Think of adjectives that best describe the images that you are drawn to, and create groupings of words that summarize your style. Are you going for elegant, simple, and contemporary? How about lush, boisterous, and playful? Identify key words like “edible landscapes” or “sustainable design” that tend to pop up repeatedly in your search. The combination of visual imagery and written description adds to the refinement of your ideas and helps to clarify design intent.

During this phase of gathering inspiration, also think about how you want to live in your landscape. Are you passionate about entertaining and crave an outdoor dining area with easy access to the kitchen? Do you daydream about summer naps in a shady hammock? Are you looking for a way to incorporate chickens into the garden? Think about how much time you want to spend maintaining your landscape. Do you want to spend a day working your garden only once or twice a season, or do you enjoy doting over tender plantings on a regular basis? If you spend the time to contemplate these questions, we will be able to help you match your design goals with your lifestyle.

Once you initiate a working relationship with Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, we will sit down with you to talk about your landscape, your ideas, and your needs and wants. Then we can start to contribute our expertise in order to help you accomplish your vision.

What is the place of cars in the garden? First let’s ask ourselves if feelings we associate with cars and driving are compatible with the home environment we want to cultivate. Instead of going straight from our car to our front door, wouldn’t we rather cultivate an intentional entry that prepares us to find the refuge of home?

The journey to refuge can begin even before we exit our cars. After driving on miles of asphalt, a new surface material tells us to start slowing down (literally and metaphorically). It is a signal that we are home. The sound of tires crunching over gravel or dully thudding over cobblestones further reinforces the sense of welcome while also alerting waiting loved ones that we have arrived.

Then there’s the challenge of elegantly folding parking into the sequence of garden spaces. Do we want to dominate a space for the exclusive use of parking? Or is there a way to overlap uses to get the most out of our landscape? How might a parking courtyard accommodate cars as well as human comfort? The relaxing sound of a water feature could encourage us to leave the hassle of the day behind. An integrated seating area could give us just another few minutes to unwind and sort the mail before stepping inside. Or perhaps after a long day, we just want a welcoming space to take a moment to watch the play of light as the sun goes down.

In some contexts, we may want to leave our cars even farther behind and out of sight. In order to take in the full splendor of our landscape, we don’t want to see any icons of the business of everyday life. Constantly catching a glimpse of our cars reminds us of work to be done, errands to be run, meetings to make…. Parking remotely gives us the opportunity to create a protracted, choreographed entry to our private places of retreat. This choreography of transition is unique to each home and landscape, responding to inherent characteristics and highlighting distinctive qualities.

To successfully create a feeling of cohesion between the architecture of our homes and our landscapes, the transition between these two living spaces requires delicate management. Whether a site is located in a semi-urban area like Eugene, Oregon, or in a more remote and rural setting, the success of a project hangs on the designers’ ability to elegantly resolve this critical transition. Landscape architects think of the transition as a gradient. The gradient is variable in thickness, transitioning from the built to the natural environment, with any number of bridging values in between. The thickness of the gradient will change depending on several factors such as the landscape context, architectural style, and the client’s desires.

The transition between home and nature may dissolve slowly over a large distance. In these cases, it may be difficult to discern where home meets garden and garden meets landscape. Common materials from the interior architecture may extend into the adjacent garden spaces, and natural stone and planting may find its way into the interior. Then, natural materials may become more dominant as the distance from the home increases. Form, like materiality, also transforms in relation to the gradient of transition. Ninety-degree angles could incrementally disintegrate until geometry melts into organic form.

On the other hand, the transition may be condensed and unfold quite quickly. If the garden itself is architectural in nature, there may not be as many incremental values of change. Consider a courtyard garden, bounded on all sides by architectural form. What is the experience of moving across the interface between interior space and garden in this context? What about the interface between an alpine home and the surrounding wilderness? Maybe in this case, the transition may only call for a careful editing of the surrounding forest. With these examples we can begin to understand how many conditions interact to shape each site’s unique transition.

The most significant intervention along the transition is exactly where and how architecture meets garden. What is the quality of that threshold? Is it marked by a physical transition from one ground plane material to another? Where does the boundary really want to be? The boundary doesn’t necessarily need to create a uniform circumference around the house. In some areas, the surrounding untamed landscape may want to come right up to the house while in other zones, the threshold moves farther afield. The resulting, undulating pattern of transition weaves context, garden, and architecture together.

What is most important is that this choreography of transition feels right and unique to each site. It is our job as landscape architects to help our clients discover an interface that is right for them and their personal architecture and garden.

Landscape architects manipulate space by carefully considering the resulting effects. We very purposefully cultivate opportunities to see a landscape with fresh eyes. At Lovinger Robertson in Eugene, Oregon, we form close working relationships with our clients in order to understand the way they want to interact with their landscapes. This understanding serves as our primary guide during the process of master planning – which in essence is an orchestration of landscape spaces that unfold in a deliberate sequence.

There are places on your property that are special. Places that you want show off to your friends. It may be a walk to get there. But we don’t want to race ahead and skip right to the big reveal. That would be a pretty boring, one note garden performance. Even a tiny courtyard garden can harbor sweet surprises and seasonal change. Why not build a whole symphony of experiences that allows your garden to show off its entire range of potential?

We move through gardens. This means that we can take advantage of the ways in which we tend to physically interact with the space around us. Wide, straight, smoothly paved pathways bounded by vegetation encourage us to move quickly through a space, rapidly getting us from here to there. Winding stone paths encourage us to slow down and enjoy the special planting jewels at our feet. Large terraces with generous seating encourage social gathering. Shady nooks invite personal retreats or close conversations.

What is the character of the journey through these spaces? What do we see as we move through the landscape – not just in our immediate space but also spaces across a distance? Do we see a long view down an allée? Are we looking across a meadow and admiring the interplay of light and shadow? Do we spy a folly on the other edge of a pond? Or maybe a cleverly placed mirror in an intimately sized space reflects a gorgeous section of our garden that is outside our cone of vision.

We can admire at a distance or be seduced to get closer through invitations to explore. A simple bridge spanning the most modest distance begs to be crossed. Giving small previews of places to be discovered whets the appetite for more. We may be walking along when we catch a glimpse through an opening in the trees or a window in a wall of something beautiful – light glinting on water’s surface, a cacophony of flowers in bloom, or a sweeping view across a valley. We remember that moment in the back of our minds as we move through different spaces. Suddenly, we round a corner and – ah! There it is!

The process of getting to the special places in our garden prepares us to stretch our enjoyment to maximum heights. The choreographed journey allows us to incrementally shed our worries, stress, and cares so that we can find peace and appreciation in our gardens over and over again.

What is truly special about growing food in our gardens? Living in Eugene, Oregon, we can easily find locally grown, delicious produce from farmers markets or CSA’s. Perhaps we feel the magic of food harvested from our gardens because the process recalls the very origins of gardens. The idea of a garden began as a place set apart, a place where we could protect and cultivate our own productive plot of land.[1] Our landscape designs started out of the need for the practical, but became integrated with the ornamental, becoming a synesthesia of the senses.

We relish the experience of producing food in our own gardens. Think of all the sensations and memories that bubble to the surface when plucking a ripe tomato from the vine. The sunned skin of the tomato is pleasantly warm to the touch, the vibrant colors sing to our eyes, the smell is intoxicating, and the taste! The taste is out of this world.

With all these temptations, we still may need to protect our gardens from hungry visitors. Practicality necessitates the creation of physical barriers between spaces. But how does an effective enclosure translate to visual form? Do we want to create a permeable barrier that we can see through freely, or do we want a something more solid? What feelings do a rustic stone wall evoke versus those of a post and rail fence? How do we create an enclosure without chopping up a landscape into disconnected chunks?

It’s important to contemplate the way we transition between the space that is within the enclosure and the space without. A garden gate signals the moment of threshold. We physically touch the gate as we open and close it. Does the action require a strong push or does it swing freely on its hinges? A gate can communicate its grandeur – announcing itself proudly – or it can rest quietly, while dutifully and excellently performing its purpose.

Aside from keeping unwanted visitors out, enclosures may also create alluring microclimates. Certain materials more readily capture and reflect the sun’s heat, allowing desirable plants on the edge of our zone to thrive instead of struggle. We also may want to minimize the effect of damaging winds with shielding elements.

Sometimes we want to create a very strong sense of separation between a vegetable garden and the surrounding landscape with enclosures – a clear division of space delineating the place of production and the place of ornament. Or we may blur that line and instead ask food-producing plants to assume the role of highly controlled ornaments, much like the kitchen gardens at the famous, historic Chateau Villandry* in France. In contrast, other individuals may wish to incorporate food-bearing plants throughout a larger garden space. Weaving fruits and vegetables into an overall planting design could create the opportunity to wander from moment to moment of alimentary delight, allowing colors and smells to guide us on our journey.

All of the practicalities of food production create a resulting look of gardens that has persisted through time. When growing food, form must follow agricultural function. University of Oregon Professor Emeritus Kenneth Helphand has coined the term “agritecture” to describe the resulting look of productive gardens. Beanpoles reach to the sky, punctuating the vertical space in regular intervals. Espaliered fruit trees form impressive green walls. Heads of cabbage sown in perfectly straight rows draw physical lines of perspective. Perhaps it is this continuity of agritecture that tugs at our collective ideas about the nature of gardens. Maybe a garden just doesn’t seem complete without the indicators of agritecture, without growing food.

[1] Hauser, Albert. "On the Origin and Meaning of Gardens." Anthos 16.1 (1977).

* Virtual Tour of the Gardens of Villandry

We were recently interviewed by the Register Guard newspaper of Eugene, OR. See the article at The Register Guard.

It is repeated here below:

By Kelly Fenley

Photos by Collin Andrew

June 19, 2014

Rainy days add up to summertime fun for Jackie Robertson. She has a pond on her country property south of Eugene that collects rainwater. Lined with clay to prevent leaks, it’s where she and friends swim, sunbathe, glide a kayak and soak up a wetlands solitude bustling with blue dragonflies, warbling birds and squiggly salamanders.

Evenings bring chorus frogs and battalions of bats on mosquito patrol. “Oh, I love it,” says Robertson, a landscape architect. “There’s so much that goes on by the pond that doesn’t happen in other places because of the wildlife that show up.” “One day I was in shock,” she thinks to add. “I was just lying there being lazy. Somehow or another, because I was so still, a blue heron didn’t realize I was a threat and landed on the dock 6 feet from me.”

Lessons learned

But this 100-foot by 60-foot pond wasn’t always such a natural oasis. When first dug out by previous owners, it had a narrow patch of land jutting into the middle, likely because a backhoe had sat there while excavating the pond into a horseshoe shape. But the problem with the peninsula was that it created growing room within the pond for self-populating plants. Cattails, wild roses, sedges and rushes infiltrated the peninsula’s shallow-water shelf and began making their own soil. “So what ended up happening, the pond started disappearing,” Robertson says.

She decided to start over.

A contractor, Dennis Cole of Dennis Cole Excavating, formed the pond into an oval shape, 9 feet deep at the center. “When we did that, we also planned for most of the sides to be quite steep, and that was so the vegetation couldn’t walk in very far,” Robertson says. Next she had Rexius line the pond with 50-pound bags of bentonite clay sourced from Eastern Oregon. When the clay gets wet, it swells and plugs leaks. “You have to line the pond, period,” exclaims Robertson, who, along with Justine Lovinger, owns Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects in Eugene. She chose clay for a balanced ecosystem and long-term ease of care, but says a synthetic or even concrete liner also would have sufficed to seal the pond. For the safety of kids, pets and wildlife, a little beach breaks up the pond’s steep rim. Kids play on the beach, made of compacted gravel topped with sand, and the shallow water provides a quick exit for wildlife in over their head.

Concrete piers for the swim dock escalated the pond’s cost, which Robertson estimates at $25,000 when including the value of her own work and expertise.

Suitable setting

Flat ground works best for most ponds, but it’s sloped topography within a perimeter of firs, cedars, Oregon ash, vine maples and bigleaf maples that channels rainwater into Robertson’s reservoir. A spillway directs overflow back into the terrain’s natural drainage. Without a spillway, Robertson notes, overflow would erode the pond’s earthen dam. She would welcome a little creek or spring for water supply, but warns that many waterways carry protections for wildlife and people irrigating downstream. “Before you build a pond at all, the correct thing to do is talk to the Water Master,” she says in reference to the state Water Resources Department. In fact storing water of any kind requires a permit from the state, unless it’s runoff from an asphalt driveway, rooftop or other impervious surface, says Scott Grew of the Water Resources Department. “All water is owned by the people of the state of Oregon,” explains Grew. Before excavating a pond to store water off the land, he says to call the department at 1-503-986-0800.

Keeping it clean

Hot summer days can evaporate Robertson’s pond at up to a quarter-inch per day. “So that’s another reason to try to have less surface area compared to depth,” she says. “The shallower ponds are going to disappear faster than a deep pond.” (Refilling a pond with well water also requires approval from the Water Resources Department, Robertson notes.) But other forces of nature help keep the pond clean. During winter, the pond’s surface temperature turns colder than water below. Quite suddenly, an “upwelling” will cause warmer water below the surface to rise, while the colder surface water sinks. When the bottom water rises, it brings the mud with it and clouds the pond, Robertson notes. But come summer, the reverse happens: water on the surface heats to the point where colder, muddy water sinks back to where it started. “So literally my pond was muddy a week ago, and now it’s clear,” Robertson says. “It just flipped in a week.”

Natural ecosystems around the pond, especially vegetation limited to shallow water, will foster beneficial organisms to control mosquitoes. Shading from trees and keeping the pond’s bottom free of organic matter, such as leaves, help to limit algae blooms and water weeds. When she must treat an algae bloom, Robertson uses a powder called GreenClean.

“One should not be disheartened if for the first two or three years (after digging a pond) you have to fight with algae,” she says. “You can’t expect a full, natural biotic system to redevelop right after you have (excavated). After a while things will start to balance out.” So long as it keeps raining, of course.

Home & Garden editor Kelly Fenley can be contacted at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter: @KFenleyRG

Pond permit

Anytime water is stored from off the land, such as from a stream, spring or even rainwater, a permit is required from the state of Oregon’s Water Resources Department. For information call 1-503-986-0800 or see www.wrd.state.or.us.

Way back in February, there was a record ice storm. Trees bent to the ground, shrubs flattened, buds coated in ice looking like candy confections.... Hopefully you were smart enough not to get rough with your plants trying to help them clear the ice, and you didn't panic to try and help them upright right after. But now it is spring. All those bent over trees are reaching again for the sky, and the flattened shrubs are back up and shooting out new growth, but the hidden damage is finally showing. Is it best to try and nurse your favorite plants back to health or give up and start over?

Here in the southern Willamette Valley in Oregon, we had a rare winter of extremes. Our maritime climate was turned twice on its head with record breaking low temperatures. The first was really early in the winter before our trees and shrubs had relaxed into dormancy. The second included temperatures in the single digits in February, far below our normal coldest winters, and topped off with a half inch coating of freezing rain that held for 3 days. We are in a very temperate zone 8 here, and are accustomed to enjoying plants that hail from near the arctic, all the way to the Mediterranean. It has been fascinating to see what failed, and what has come back. Most deciduous shrubs and trees know how to prepare for the cold. They pull their saps back within their thick bark, shed their tender leaves and go to sleep. Our tall conifers drop their branches to their sides and let the snow and ice slide to the forest floor. Most of the perennials sacrifice everything above ground routinely each winter, counting on the soil to protect the life force in the roots. It seems the most vulnerable plants have been the broad-leaf evergreens who normally thrive in our wet 40-degree winter days, preparing flower buds for early spring blooms. These guys really suffered. The Sweet Box (Sarcoccoca confuse), the Star Jasmine (Traechelospermum jasminoides), and even the David’s Viburnum (Viburnum davidii) – all reliable long lived plants here - died slowly from the tips toward the trunks, and the cause was long vertical splits in the bark caused by freeze. Branches turned black and hard. Poor things, they lost the continuity of the vessels that carry nutrients and were left open to disease.

So obviously, those branches aren’t going to recover. Step one. Prune them back to a healthy branch or leaf node and see if they bud out in the spring. Step two, spring has arrived and either you are amazed at how your poor shrub is sprouting from the base of the still healthy branches, or it has obviously just not made it. But what to do if it is a third alternative and it’s trying hard, but still looks pretty crummy with the graduation party quickly approaching? Before you rip it out, check in with the nurseries. They had the same bad winter! Is a replacement even available that will make you happy? Remember however the advice that I received one year from a trusted landscaper. A temporary blank spot in the garden is far more attractive than a near dead specimen. Sometimes you have to let go of an old attachment to make room for a new adventure!

Living in the scenic Pacific Northwest, we are surrounded by a lush environment that is the habitat for many native plants and animals. Keeping our environment free of toxins, encouraging native plant diversity and reducing waste are a few common concerns for Eugene, Oregon gardeners. When incorporating gardening into a landscape design, it is difficult to balance beauty with ecological concerns. Below we have a few tips so that you can do both.

Plan planting based on botanicals that naturally grow in the region so they will be well suited for the climate and are less likely to need fertilizers and pesticides.

Keep plants that love sun in sunny areas and shady-loving plants in the shade so they will do well and there will be less upkeep.

Water in the morning. Not only will this be more economical so that water doesn’t evaporate before it is able to soak into the ground and reach the roots, but it also is supposed to eliminate some diseases that need moisture and can’t survive in the heat of the day.

Make or buy natural pesticides made from garlic, chili powder, cloves or eucalyptus, which pests do not like.

Use a natural pesticide like horticultural oil. A commercial brand like Pure Spray coats insects with oil and suffocates them. It doesn’t harm birds, bees or the plants.

For a natural fungicide, try baking soda. Or for a commercial brand, try Green Cure.

Boiling water can be applied to weeds if other plants are not nearby like between stones.

Planting flowers that yield nectar will increase healthy or beneficial insect populations, which will in effect reduce pest populations.

Investigate whether materials like wood in a fence or deck are sustainably sourced (wood certified as sustainably harvested by the Forest Stewardship Council).

Collect water with a rain barrel.

Compost.

Buy local. Using local products and services cuts down on the distance of travel, which reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Purchase post-consumer or post-industrial materials that can easily be recycled later.

Use recycled materials. Flooring and even paint can be recycled and reused. Buy used flowerpots and planters instead of new.

Reuse salvaged materials. Whether you find these materials locally or online, they are good for the environment—and your pocket.

In the market for a new attraction out back without a total overhaul? Landscaping ideas can be as little or as big as your heart (and wallet) desire. If a small addition is all you are looking for, a fire pit may be just what the landscape architect ordered.

Depending on your existing landscape design and the type of project you’re willing to undertake, you may find something as simple as a decorative, wood-fueled fire bowl or something as extravagant as a built-in, propane-fueled fireplace with glistening fire glass. Decide what is right for your residence in Eugene, Oregon.

When deciding what will work best for your setup, there are a few important aspects you’ll want to consider:

First and foremost, your budget. There is no sense it getting all worked up about a particular plan just to determine there’s no way to fund it. Establishing a budget first will help reign in your ideas and ensure you don’t get in over your head. Depending on your plan, you may be able to incorporate phased upgrades, so you don’t need to bear the cost all at once.

Space/location: Whether you have acres of forest and rolling hills, or a contemporary condo downtown with a small patio, there’s surely something to suit your needs. Deciding how much space you’re willing to dedicate and the best locations to work with, will help you hone in on your options. It’s important to consider what purpose you want this fiery addition to serve. Are you the first one to throw a celebratory barbeque when we get three consecutive days of sunshine or do you prefer to cozy up for a quiet night in with someone special?

Fuel Source: Deciding whether you prefer the convenience and clean burn of gas or propane, or you relish the smoky air of a wood fire pit on a cool summer night, can be a tough decision but one that you’ll need to establish early on.

Whatever your decisions may be, now is the time to get that fireball rolling. Long summer days and cool summer nights will be here before you know it!

As winter approaches, it can become a challenge to maintain your garden. Many plants fail to flourish in the onslaught of heavy rains and precipitation, primarily because of excess water and lack of oxygen. While some plants struggle to survive in Eugene’s wet winter climate, others thrive. Here is a list of several plants that perform well in wet winter soil:

The Big Leaf Maple tree is an elegant and stately tree native to the Willamette Valley that provides cool shade in the summer and grows large leaves which can be composted or used to curb weed growth.

Hellebores are beautiful flowers that are able to withstand extreme weather.

Mock Orange is a shrub that supplies food and shelter to birds while also yielding beautiful white flowers.

Tulips can be planted in the fall, as can daffodils and hyacinths. These spring-flowering bulbs are beautiful and capable of withstanding Eugene’s winter climate.

If you grow your own vegetables, fall planting season is also a good time to consider next summer’s harvest (garlic, for example). It is also appropriate to transplant trees and shrubs from your landscape at this time.

The Willamette Valley is rich in color and vegetation as a result of frequent rains and natural underground water springs, but occasionally aspects of this kind of climate can hinder the vitality of a homeowner’s landscape. An abundance of precipitation coupled with an inefficient drainage system will result in soggy lawns and garden beds at best, and in the worst case can result in unhealthy plants, a ruined lawn and a damaged foundation.

Proper exterior drainage diverts water away from the home, yard and landscape, and requires careful evaluation of the site’s natural landscape and climate. In concert with this evaluation, appropriate decisions will be made regarding various drainage options and which of these options are best suited to your home’s landscape design. We invite you to explore a number of drains that can be installed to facilitate proper drainage:

French drains, wrapped in landscape fabric and masked in rock, offer a subtle solution for homes with raised planters.

Area or floor drains are placed in yards with shallow spaces that collect water during heavy rains as a means of preventing mosquito growth and foundation damage.

A gutter with a downspout that drains away from the home and yard is a necessary staple for homeowners who wish to protect their home from interior and exterior water damage.

Foundation drains are a requirement for new construction, but older homes may need to have a foundation drain installed on the edge of or beneath the foundation.

Channel drains protect your lawn and garden from patio runoff and are long channels in a concrete surface that allow water to filter into the pipes below which direct the flow of precipitation away from the home and landscape.

At Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, we take even the smallest details into consideration. One of our many priorities is to design a functional drainage system along with a master design plan that together will culminate in a practical and timeless landscape design.

We can think of the final planting design as the curtains, carpets and drapes of outdoor living spaces. Yet even when beginning general master planning for a site, the size, texture, color, and translucency or opacity of planting design should be considered in the earliest schematic design of outdoor rooms. Plants can form the floor, the walls and even the ceiling of an outdoor space. Tree trunks are columns supporting a roof of greenery. Is that overhead texture dense, private and intimate? Dappled and shimmering? Or soaring and infinite like the fir forests that are native to our region? Or should it just be the sky? These are just a few of the myriad questions that come into play in understanding the effect of planting design through the seasons and over time as the garden matures.

The majority of homes in America boast front porches, whether they are simple and modest or elegant and expansive in design. But, why? What is it about the porch that has resulted in its reign as a standard commodity in North American landscape architecture?

The name Andrew Jackson Downing carries with it the answers to such questions. Downing was not only a dedicated landscape designer, horticulturist, ad writer, but also a pioneer of American landscape architecture. He is considered by many to be largely responsible for the popularization of the front porch, because he widely publicized the notion that the feature serves as a necessary intermediary between nature and the home.

According to Downing, a porch “serves both as a note of preparation, and an effectual shelter and protection to the entrance” of a home. This brilliant landscape architect perceived the porch as an important addition to the home that not only establishes continuity between the home and the land, but that also invites one to admire and enjoy nature more comfortably.

Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects share in Downing’s passion for establishing unity between the home, those who dwell within it, and the surrounding landscape. If you wish to create a cohesive residential, commercial, or institutional space, contact Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects today. Through our careful three-step process of analysis, design, and installation, we will gladly work with you to plan and actualize landscape and architectural designs that reflect your desires.

Sources:

A treatise on the theory and practice of landscape gardening, adapted to North America; with a view to the improvement of country residences ... with remarks on rural architecture. By the late A.J. Downing, esq.

Downing, A. J. (Andrew Jackson), 1815-1852., Sargent, Henry Winthrop, 1810-1882.

New York: A.O. Moore & co., 1859.

Why do we build retaining walls?

Building a retaining wall is a cost-effective and attractive solution that accommodates – or manufactures – elevation changes in the landscape of your yard. This practical feature serves many purposes, some of which are often overlooked.

A retaining wall can form the framework in which perfectly scaled outdoor living spaces are carved into hillsides. They can add character to raised gardens as well, and keep soil from washing away during watering or rain showers. The retaining wall can renew structural integrity along roadways that have been built near waterways. It may form a bench while containing an above-ground water feature, or a balcony embracing a terrace with a view. But regardless of its function, great spatial design and the use of appropriate materials for the architecture and context of the site should tell the story of that function in a beautiful and meaningful way.

At Lovinger Robertson Landscape Architects, we take great pride in the efficacy of our flexible, detailed, and thoughtful design process. We employ a tried and true three-step process that encompasses the following:

These three steps, prudently executed, come together to culminate in a landscape rich in character and aesthetic appeal.